Inconsistent math to live by

Siddhartha Gunti

Logical Intro

The thesis for why tech folks should learn the philosophy behind math-

I was really into math/ logic growing up. My love for coding and system design was a logical and natural extension of my love for math.

But after a point, the role of math in my life fizzled out. And I am not alone. After a point, the only folks in touch with math are AI/ ML folks. Everyone else got into the rote of learning gimmicks or boiled-down processes. We stopped learning and being in touch with the atoms of logic.

Studying number theory made us love Math/ Logic. Learning programming languages and recursion made us love Coding/ System design. In the next phases of life. Before we spend more time understanding philosophy/ spirituality/ consciousness/ art. I believe there is a catalyst missing.

As far as philosophy, spirituality, consciousness, or art are concerned, I am a nobody. I don't have any answers. In fact, I don't even know what I mean by those four words I just used.

I had a discussion with one of the smartest engineers I worked with. Is coding art? My stance was yes. The friend's stance was no. I didn't have a solid answer to explain my reasoning—just a fleeting, vague and unexplainable feeling in my head.

Over the last five years, I realized I am cornering around a thesis. A thesis for not the answer but the toolkit I need before proceeding to the next phase of my life. This toolkit I am dubbing 'Mathematical Philosophy'. Before I delve into what and why we need to study "mathematical philosophy", let me give a gist of how I stumbled into this-

I spent a reasonable amount of time designing different system architectures for Adaface. These solutions and problem statements often left me with the magic of logic. The magic I used to feel back when I tinkered with math.

I read books which structured what I was feeling more concretely. The main books are

- Fermat's Enigma

- The Code Book

- Quantum computing since Democritus

- Godel Escher Bach

The more I read these books, the more I realized that they need to be condensed into an easy form. A form that folks in tech should pick up in their 20s or 30s.

So, here's the 'why.'

- Get better at structured thinking. The core of mathematics has always been atoms, axioms and structured processes. These are the core of most art we still do in our careers. System design and coding are just modern workplace forms of math and logic. Learning to design systems from scratch drives us to actual problem-solving. Instead of rote solution copying.

- Build a toolkit for philosophy. As we age, we ponder topics like existential crisis and philosophy. Throughout history, mathematics and philosophy often went hand in hand. Many mathematicians were philosophers (and vice versa). It only makes sense to rely on math to build the toolkit to understand these complex concepts.

Now as to the 'what'.

These are the slices that I want to put together. Each segment fits into one of the why's.

- Math Basics through the lens of stories and failures

- Nuggets of philosophy in recursions, paradoxes and loops

- Functional programming as an example of structured logic

- A different way of looking at proofs and theorems

- Conversational trees as an example of recursive systems

- An existential crisis in math- Godel's incompleteness theorem

- Looking at life in a non-deterministic and probabilistic way

- RSA algorithm as an example of structured logic and art

- Designing a REPL system as an example of structured design

- Some ideas I am still mulling over (Blockchain paper? LLMs? Quantum?)

In and out between the chapters, I plan to sprinkle some inspiring stories of mathematicians. The idea is to keep each chapter short and easy to understand. So that it can work as a general read for everyone in "tech". The easy the book is, the more vague we can leave the definition of what "tech" is.

What do you think?

Philosophical intro

When I wanted to introduce the book, I came up with two different versions. Here's the weirder one.

Ever heard this meme/ joke that the brain named itself? Let me expand on that point a bit. Humans named rabbits. Rabbits themselves don't care about the word "rabbits". It's something humans made to refer to an external entity. The same way humans came up with the term "Earth", the entity where they belong. Now here's where things get interesting. "Humans" named themselves "humans". This is one argument for consciousness—the ability to refer to oneself.

But humans didn't name themselves humans. We can zoom in a level and say the consciousness part belongs to the brain. Brains named external entities like "hands". Brains named the entity that they are part of "humans". In the same way, we said, humans named Earth.

We can keep on zooming into this kind of discussion. But let's segue here into a different level of discussion. And say at the centre of the brain lies intelligence and consciousness.

Intelligence also feels mathematical. We consider it as logic. It has duality. It can draw lines between the internal self and external others. It can say right from wrong. It can say 2 + 2 rabbits = 4 rabbits. We built computers with the bare bones of this intelligence. 1s and 0s. Now, when we talk about "artificial intelligence", what do we mean? Do we mean a formal system that computes so fast that it is the same or better than a human in all "intelligent" things?

Godel says that any system built out of logical methods will be incomplete. Because it will have statements about itself that the system can't say are true or false. Thus breaking its duality. So however fast the "AI" is, it won't be able to refer itself completely and consistently. Which brings us to consciousness.

Is that what consciousness is? Is it the feeling or ability to refer to ourselves? It's our 'conscious' mind about to understand itself in this world. And that understanding has no dual answers? It can't have statements that fit into our true/ false way of viewing the world. These questions can segue into philosophy. But before we do that,

There are three related and interesting questions here around Gen-AI:

- Are we saying we humans are special because we are intelligent and conscious?

- How good and active is our consciousness's ability to refer to and make peace with I?

- So if we can design the most portions of "being" a day-to-day human and club them with a sufficiently faster intelligence. Will we be able to distinguish this intelligence as not human? We can input Chat-GPT with an instruction that "you are a soft-speaking person", and it starts speaking softly. It is not that far off that we can extend the number and type of instructions. To the point that, for most practical purposes, we might not be able to distinguish it from a human?

Coming back. In the first intro, I gave two reasons why someone in tech should read this. First is to improve at structured system design, and second is to understand mathematical philosophy. You might ask- why have two motivations? But I think there is a journey from one 'why' to the other.

So far, logical learning and formal systems have got us into coding. We want to nurture and relish that skill. That's where we board the bus that is this book. System design and probabilities are just a reminder of how delicious that skill is. That is the core part of this book's journey. The destination is where we realize formal systems won't answer everything about life. The maximum they get us to is to ask interesting questions about consciousness. And that's where the last stop for the logical bus is. To explore the next stops, like philosophy, we need to internalize how far the logical bus can go.

The worst-case hope is that you fall in love with code/ math/ system design, yet again. The best-case hope is that we build our mental toolkit to kick off the journey into philosophy. In terms of categories, here's what the book is going to do:

- Remind the fun examples and stories of Math/ Logic.

- Some fun examples of recursion used in Coding/ System designing.

- Looking at probability and algorithms as a base for mental models.

- Creating a computer based on formal systems. Looking at why such a computer can't talk about itself.

- Some fun discussions of brilliant system designs.

Conversational Trees

We had two phases for chatbots. The first one was when Facebook created a buzz around chatbots. It died quickly because of how boring and ineffective those chatbots were.

The second phase is now. With GPT, chatbots are back with renewed vigour.

Between these two phases, when everyone wrote out chatbots as not a thing. We at Adaface created a chatbot to conduct a technical test. We often received reviews calling our bot "innovative" and "human-like". Behind the scenes, there was no AI. There was no NLP. And there was no human. There were decision trees designed to conduct an adaptive conversation.

This chapter is a slice of how we built the chatbot. I simplified the problem statement so that the discussion could be wrapped up in a single chapter.

Before I kick off, a short note: I have written this content to go along with my book. You can read the current version of the book (including this chapter) here - inconsistent-math-to-live-by.

Back to business:

Let's design a chatbot that conducts a technical test. Here's the core functionality that we need:

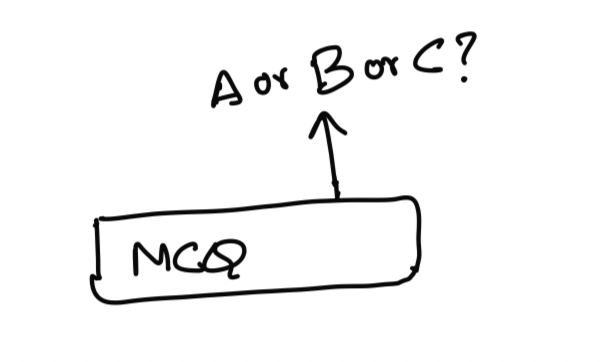

Ability to ask MCQ questions to candidates.

Candidates should be able to attempt the MCQ question twice.

The bot should respond with a contextual hint the first time they make a mistake.

Remember and reproduce the state of the chat. State here refers to two portions.

- Chat history

- Chat position, i.e., if the candidate is in attempt #2 of question #3, reloading should keep the candidate in the same place.

Here's the second-level breakdown of the chat functionality:

- Chat needs to support text input from the candidate

- Chat needs to support MCQ option style input from the candidate

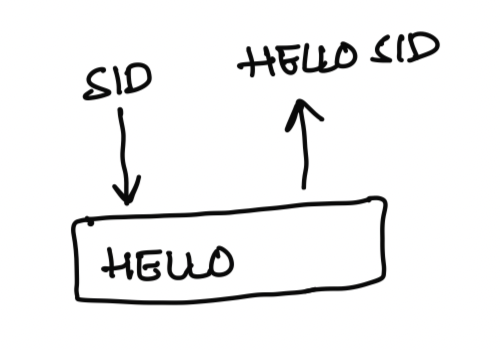

At the atomic level, here's what the bot is doing:

- It presents information to the user (ex: greeting - "Hi! What is your name?" or "What is 2 + 3?")

- It expects input from the user (ex: "Siddhartha" or "5" as a response to the above questions)

- Depending on the user's input, it decides what to do next (i.e, present information or expect input)

One structure that comes to mind if you look at the bot actions at the atomic level is tree-based. Now let's design a tree-like system to support this:

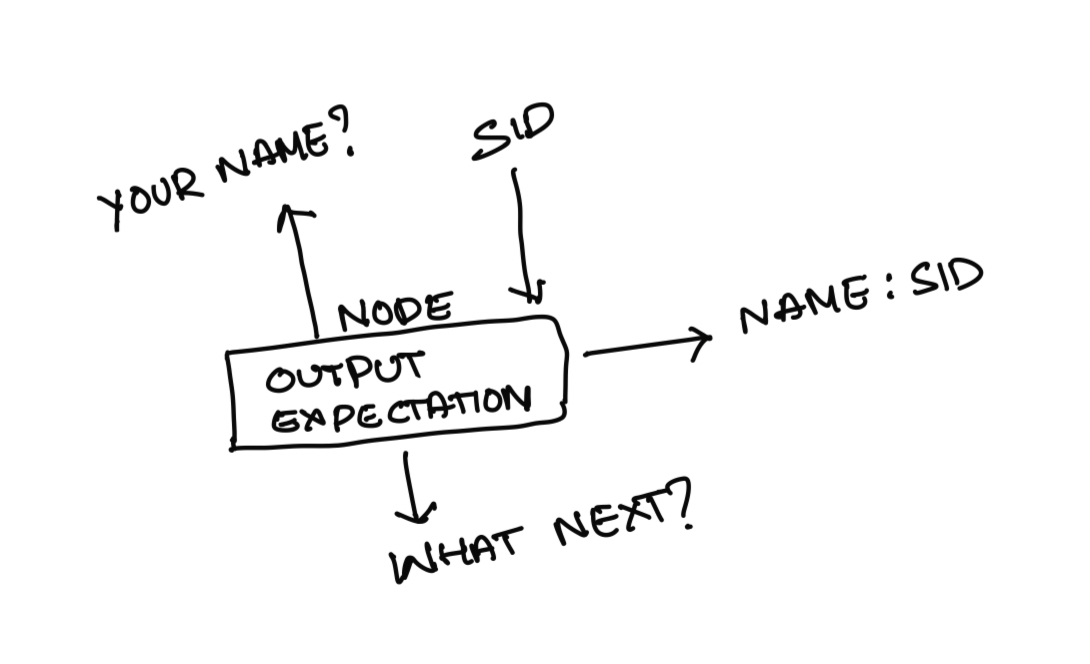

First, let's try to design the simple "nodes" of our tree structure:

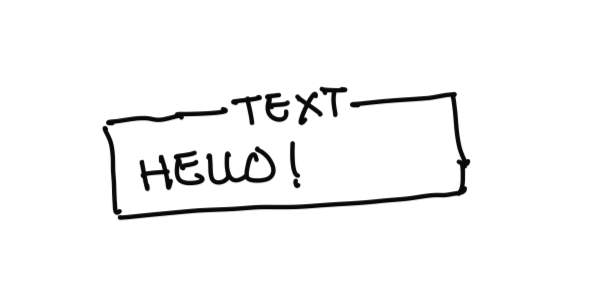

// Output node:

class Output {

constructor({ type, data }) {

this.type = type; // different type of outputs like 'text', 'image'

this.data = data; // actual data like 'Hello!', '<url to image>'

}

}

Simple examples of above node are

new Output({ type: "text", data: "Hello World!" })

Now let's expand this node with a "ui" attribute. This UI is equivalent to the UI that the user sees. This UI should be able to present information to user and accept information from user. We expect UI to have a pre-defined function called "emitOutput". Any node with access to UI can use this function to present information to the user.

class Output {

constructor({ type, data }) {

this.type = type;

this.data = data;

}

assign({ ui }) {

this.ui = ui;

}

execute() {

this.ui.emitOutput({

type: this.type,

data: this.data

});

}

}

Now UI can assign itself to this node by calling .assign(). When it wants to "execute" this node, it can call "execute" which in turn calls its own emitOutput function. Which in turn shows the output to the user.

So far, This functionality works well for simple output's like "Hello!". But what if we want to keep it dynamic?

For example, We want to say "Hello

Now let's raise the responsibility of the "ui" to accommodate this. One: UI maintains a "data store". When the output is emitted, individual nodes can feed into this information to create dynamic output. Two: Along with type and data, there can be a function which takes in type, data and data store as inputs to decide the output.

Let’s put it together:

class Output {

constructor({ type, data, fn }) {

this.type = type;

this.data = data;

this.fn = fn;

}

assign({ ui }) {

this.ui = ui;

}

execute() {

this.ui.emitOutput(this.fn({

dataStore: this.ui.getDataStore(),

type: this.type,

data: this.data,

}));

}

}

This makes our outputs more versatile. For example, here's a dynamic output:

new Output({

type: "text",

data: "Hello, ",

fn: ({type, data, dataStore}) => {

return {

type,

data: data + dataStore.name

}

}

});

Now let's create a node that "expects" information from the user. This can be the text input from the user (like their name). Or it can be an MCQ option (one of the options for the MCQ question like "A", "B", "C", etc.)

class Expectation {

constructor({ type, data, fn }) {

this.type = type; // "text" or "MCQ"

this.data = data; // any relevant information that UI needs to create input UI like max 100 characters or one among "A", "B", "C" etc

this.fn = fn; // dynamic function using which actual type and data can be modified.

}

assign({ ui }) {

this.ui = ui;

}

execute() {

this.ui.emitExpectation(this.fn({

dataStore: this.ui.getDataStore(),

type: this.type,

data: this.data,

}));

}

}

Now, let's go one step higher. Nodes that output messages to UI and then expect some input from the user.

class Node {

constructor({

output, expectation

}) {

this.output = output;

this.expectation = expectation;

}

assign({ ui }) {

this.ui = ui;

if (this.output) {

this.output.assign({ ui });

}

if (this.expectation) {

this.expectation.assign({ ui });

}

}

execute() {

if (this.output) {

this.output.execute();

}

if (this.expectation) {

this.expectation.execute();

}

}

}

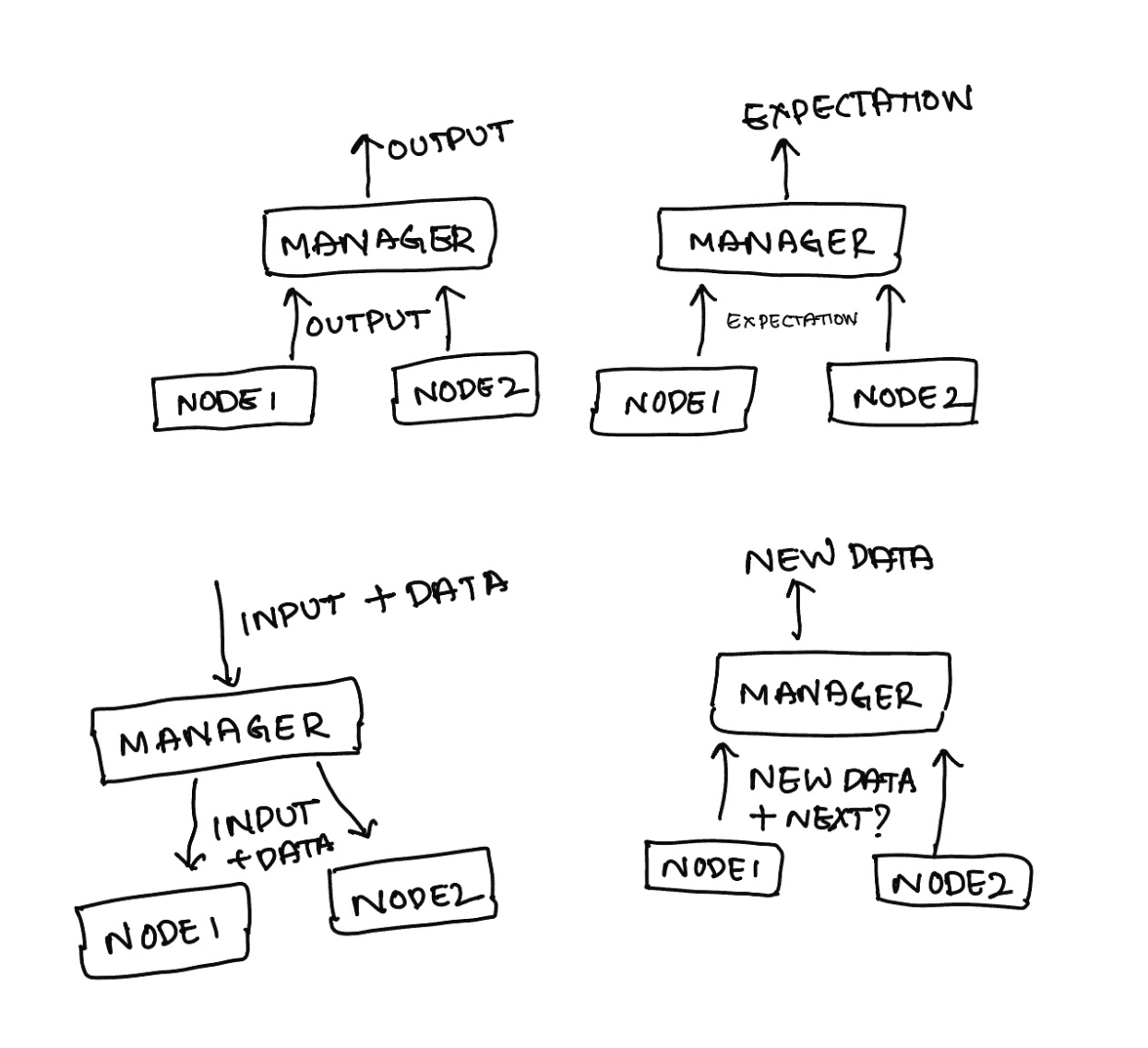

Now let's add the functionality of receiving user input (expectation from user fulfilled). Based on the user's input, these nodes do two things. One- might learn some new information about the user, like the user's name. Or the user's answer to a question (right or wrong). And Two- decides when to move to the next node.

To facilitate these two core functionalities of our atom, let's create a "decisionMaker" function. This function does these-

Accepts user input + data store from UI and decides if there is any new data (dubbed "miniDataStore") that it learnt.

Merge this new learning with the UI's data store so that other nodes can use this information (Ex: Node 1 learnt that the user's name is "Siddhartha". Node 100 should be able to say, "Bye! Siddhartha".

Decides the next step:

- Move to a new node with some name (based on user input. For example: if the output was "Do you like Java or JavaScript?" and if the user's input was "Java", then the next node would be "Q1 of java").

- If there is no new node to move to, inform UI that it can end the session.

The job of 2 & 3 both depend on the user's input and happen at the same time. So we can handle them both by adding a "decisionMaker" function as the node's input.

To serve these jobs, we expect the UI to have

- A function to merge the miniDataStore into its own data store. (let's call it mergeMiniDataStore)

- A function to move to the next node by name. (let's call it moveToNextNode)

- A function to end the session. (let's call it endSession)

Let’s put this together with these assumptions now:

class Node {

constructor({

output, expectation, decisionMaker

}) {

this.output = output;

this.expectation = expectation;

this.decisionMaker = decisionMaker;

}

assign({ ui }) {

this.ui = ui;

if (this.output) {

this.output.assign({ ui });

}

if (this.expectation) {

this.expectation.assign({ ui });

}

}

execute() {

if (this.output) {

this.output.execute();

}

if (this.expectation) {

this.expectation.execute();

}

// If this is a node which just presents information to user

// we don't need to wait for user's input. There is nothing to wait for.

if (!this.expectation) {

this.onInput({ input: null });

}

}

// process user's input

onInput({ input }) {

const { nextNode, miniDataStore } = this.decisionMaker({

input,

dataStore: this.ui.getDataStore(),

});

if (miniDataStore) {

this.ui.mergeMiniDataStore({

miniDataStore,

});

}

if (nextNode) {

this.ui.moveToNextNode(nextNode);

} else {

this.ui.endSession();

}

}

}

This node becomes a fundamental atom for our system. For example, a flow like:

- Bot responding, "Hi! what's your name?"

- Bot awaiting user's text input

is equivalent to a single node with one output and one expectation. If we have to keep the fundamental atom as is. When there is no expectation, instead of using output, we can simply use node by setting expectation as null.

For the UI to use this atom, it has to maintain a set of nodes by their names (so that when "moveToNextNode" happens, it can switch to the new node and "execute" on the new node. Also, if you notice, the UI needs to know which node is the first! So when the session is new, it knows which node to start with.

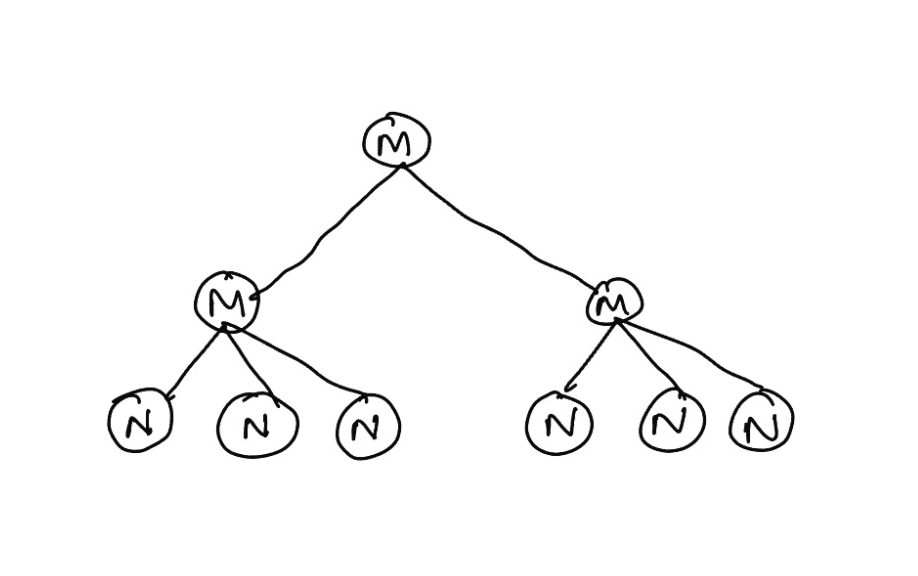

Since a chat will have hundreds and possibly thousands of nodes, let's create an intermediate "node" that can act as a UI as well as a node. (picture that we have discussed leaves of a tree so far. Now we are going one step higher). Why should this intermediary node be a UI AND a node?

- Why a node? - so that other nodes can be its parent

- Why a UI? - so that all its children can "imagine" that it is the UI and call UI's functions on it. But since the intermediate node is itself a node, it will percolate this information one level higher! Neat right?

Let's call this intermediary node-cum-ui a "manager" and start building:

To keep matters simple, we will keep this manager node with null output and expectation so that the core of its work is to manage its nodes.

class Manager extends Node {

constructor({

nodeMap, rootNode, decisionMaker

}) {

super({ output: null, expectation: null, decisionMaker });

this.nodeMap = nodeMap;

this.rootNode = rootNode;

}

emitOutput({ type, data }) {

// Need to percolate information to it's own parent node (which can be another manager or ui)

}

assign({ ui }) {

if (ui) {

this.ui = ui;

}

}

emitExpectation({ type, data }) {

// Need to percolate information to it's own parent node (which can be another manager or ui)

}

execute() {

// Execute the current active node

}

/* responsibilities of being a UI kick in here. */

mergeMiniDataStore({ miniDataStore }) {

// Need to merge this new update with the global store

}

getDataStore() {

// Return the global data store

}

moveToNextNode(node) {

// Move to next node from the node map

// Ensure this manager node assigns itself as "ui" to the next node

// Execute this new node to move things forward

}

onInput({ input }) {

// Received user's input from parent. Since there is no expectation here, the node which is waiting for input is the current active node. Pass the input to that node.

}

endSession() {

// The job of this manager has come to an end.

// Since this itself is a node, this part is equivalent to

// ... onInput of a node.

// i.e, merge any new learnings to global store

// decide which next "node" to go to and ask the parent to move to that node

// if there is no such manager to go to, end the session one level higher

}

}

If you go through the logic we need above, we realize two requirements:

- Managers are connected to other managers like a tree (each manager inside itself has a tree of managers :D)

- There is something called an “active” or “current” node.

Let’s put these together:

class Manager extends Node {

constructor({

nodeMap, rootNode, decisionMaker, currentNode

}) {

super({ output: null, expectation: null, decisionMaker });

this.nodeMap = nodeMap;

this.rootNode = rootNode;

this.currentNode = currentNode;

}

getNodeFromName(name) {

return this.nodeMap[name];

}

emitOutput({ type, data }) {

this.ui.emitOutput({

type,

data

})

}

assign({ ui }) {

if (ui) {

this.ui = ui;

}

}

emitExpectation({ type, data }) {

this.ui.emitExpectation({

type,

data

})

}

execute() {

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).execute();

}

/* responsibilities of being a UI kick in here. */

mergeMiniDataStore({ miniDataStore }) {

this.ui.mergeMiniDataStore({ miniDataStore });

}

getDataStore() {

return this.ui.getDataStore();

}

moveToNextNode(node) {

this.currentNode = node;

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).assign({ ui: this });

this.execute();

}

onInput({ input }) {

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).onInput({ input });

}

endSession() {

const { nextNode, miniDataStore } = this.decisionMaker({

dataStore: this.getDataStore(),

});

if (miniDataStore) {

this.mergeMiniDataStore({

miniDataStore,

});

}

if (nextNode) {

this.currentNode = this.rootNode;

this.ui.moveToNextNode(nextNode);

} else {

this.currentNode = this.rootNode;

this.ui.endSession();

}

}

}

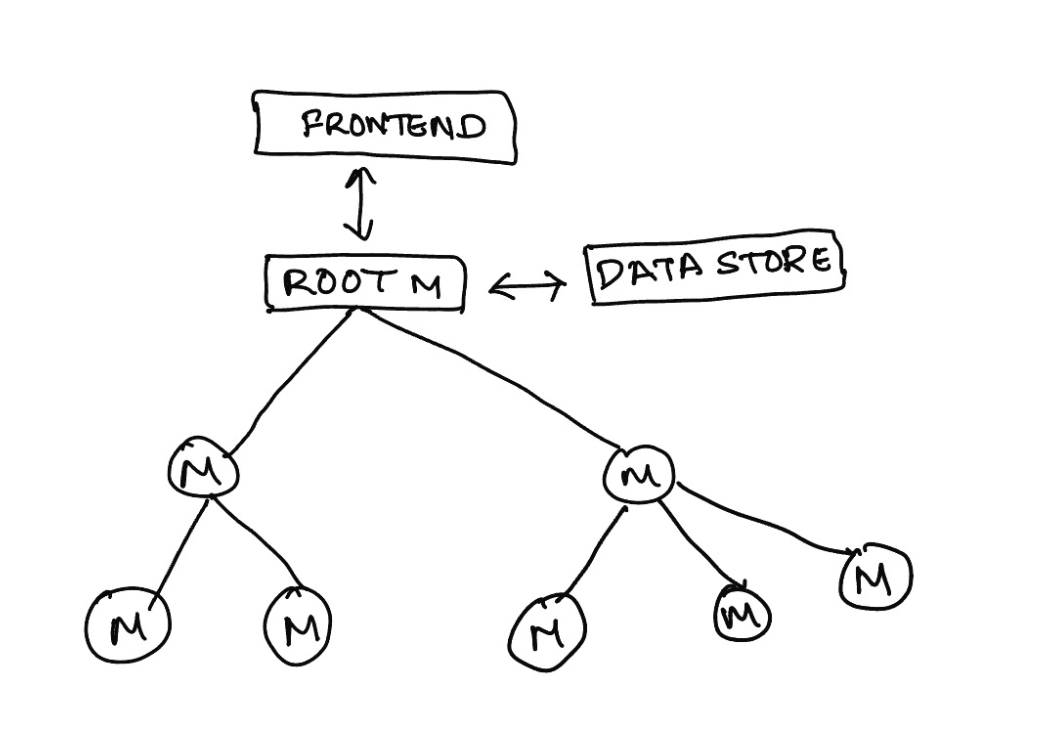

Go through the logic carefully here. Nothing fancy but just one step higher than the previous node. But this node is not exactly the UI node, yet. It is just enough to work with another "ui" node set in the constructor. But it in itself can't be a UI node. Because someone still needs to provide "dataStore" that every node and manager hungrily asks for. Some UI node has to finally perform mergeMiniDataStore that every manager is percolating to the top. And someone has to perform "endSession", whatever that endSession is.

Here is an interesting question, we know that every manager is a UI. And since it's a tree, its parent is another manager/ UI and so on, until the tree reaches the top. And at the top sits the actual UI node. Given the current manager code, how do you know if the current manager is the UI at the top or if it is any other manager?

this.ui will be null :D Because there is no UI to assign to as such!

Let's use this knowledge to amp up our manager to work as the main root UI.

class Manager extends Node {

constructor({

nodeMap, rootNode, decisionMaker,

}) {

super({ output: null, expectation: null, decisionMaker });

this.nodeMap = nodeMap;

this.rootNode = rootNode;

this.currentNode = rootNode;

}

// new helper

isRootUI() {

return !this.ui;

}

getNodeFromName(name) {

return this.nodeMap[name];

}

emitOutput({ type, data }) {

if (this.isRootUI()) {

// this is where handoff to frontend happens.

// i.e, actually show it to the user in webpage or iOS app or whatever the frontend is

} else {

this.ui.emitOutput({

type,

data

})

}

}

assign({ ui, dataStore }) {

if (ui) {

this.ui = ui;

}

// giving a way to maintain global datastore at root UI

if (dataStore) {

this.dataStore = dataStore;

}

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).assign({ ui: this });

}

emitExpectation({ type, data }) {

if (this.isRootUI()) {

// This is where we need to hand it off to the actual frontend to showcase that input box or buttons to collect user input

} else {

this.ui.emitExpectation({

type,

data

})

}

}

execute() {

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).execute();

}

mergeMiniDataStore({ miniDataStore }) {

if (this.isRootUI()) {

// update the global datastore

this.dataStore = Object.assign({}, this.dataStore, miniDataStore);

} else {

this.ui.mergeMiniDataStore({ miniDataStore });

}

}

getDataStore() {

// return the actual object

if (this.isRootUI()) {

return this.dataStore;

}

return this.ui.getDataStore();

}

moveToNextNode(node) {

this.currentNode = node;

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).assign({ ui: this });

this.execute();

}

onInput({ input }) {

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).onInput({ input });

}

endSession() {

const { nextNode, miniDataStore } = this.decisionMaker({

dataStore: this.getDataStore(),

});

if (miniDataStore) {

this.mergeMiniDataStore({

miniDataStore,

});

}

if (nextNode) {

this.currentNode = this.rootNode;

this.ui.moveToNextNode(nextNode);

} else if (this.isRootUI()) {

// We actually have to mark this session as ended here.

// i.e, close down the session

// This is where we inform the frontend to wrap it up.

// Wrap it up might mean different things for different apps

// Might be a exit screen or same chat session with no more inputs allowed

} else {

this.currentNode = this.rootNode;

this.ui.endSession();

}

}

}

Now if you see, the remaining pieces talk about the "frontend". i.e., actually showing information to the user or actually collecting information from the user. This "frontend" can be anything - from an iOS chat application to a simple web or terminal console application. What the "frontend" is doesn't matter.

But we can see what functionality the "frontend" needs to implement:

- showOutputToUser

- getInputFromUser

- endUserSession

- startUserSession

To make it easier, we will assume "frontend" is an input to the root node and implements these features. So we can freeze our decision tree code.

class Manager extends Node {

constructor({

nodeMap, rootNode, decisionMaker, frontend

}) {

super({ output: null, expectation: null, decisionMaker });

this.nodeMap = nodeMap;

this.rootNode = rootNode;

this.currentNode = rootNode;

this.frontend = frontend;

}

// new helper

isRootUI() {

return !this.ui;

}

getNodeFromName(name) {

return this.nodeMap[name];

}

emitOutput({ type, data }) {

if (this.isRootUI()) {

this.frontend.showOutputToUser({

type,

data

})

} else {

this.ui.emitOutput({

type,

data

})

}

}

assign({ ui, dataStore }) {

if (ui) {

this.ui = ui;

}

if (dataStore) {

this.dataStore = dataStore;

}

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).assign({ ui: this });

}

emitExpectation({ type, data }) {

if (this.isRootUI()) {

this.frontend.getInputFromUser({

type,

data

})

} else {

this.ui.emitExpectation({

type,

data

})

}

}

execute() {

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).execute();

}

mergeMiniDataStore({ miniDataStore }) {

if (this.isRootUI()) {

this.dataStore = Object.assign({}, this.dataStore, miniDataStore);

} else {

this.ui.mergeMiniDataStore({ miniDataStore });

}

}

getDataStore() {

if (this.isRootUI()) {

return this.dataStore;

}

return this.ui.getDataStore();

}

moveToNextNode(node) {

this.currentNode = node;

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).assign({ ui: this });

this.execute();

}

onInput({ input }) {

this.getNodeFromName(this.currentNode).onInput({ input });

}

endSession() {

const { nextNode, miniDataStore } = this.decisionMaker({

dataStore: this.getDataStore(),

});

if (miniDataStore) {

this.mergeMiniDataStore({

miniDataStore,

});

}

if (nextNode) {

this.currentNode = this.rootNode;

this.ui.moveToNextNode(nextNode);

} else if (this.isRootUI()) {

this.frontend.endUserSession();

} else {

this.currentNode = this.rootNode;

this.ui.endSession();

}

}

}

That's it. That's our entire decision tree in its full glory. To test this, let's do two things

- Create a simple decision tree for a few MCQs

- Create a vanilla frontend web implementation

The flow we will build out will look like this:

Start session

Respond: "What is your name?"

- Accept: text from the user

Respond: "Hello!

” Respond: "What are you comfortable with?"

- Accept: One of "Java" or "JavaScript"

Respond: "Sweet."

Respond: "What is 1 + 2 in Java?" (if the previous response is "Java")

- Accept: text

- Respond: "Correct!" or "You are higher" or "You are lower" depending on the user's input

- Accept: text if the previous attempt is not correct and if it is < 3 attempts.

Respond: "What is 1 + 2 in JavaScript?" (if the previous response is "JavaScript")

- The rest of the flow remains the same as in Java

Respond: "That's it from my end. Hope you liked the chat

." End session

A vanilla web app “frontend” code wrapper looks like this:

var frontend = {

showOutputToUser: ({ type, data }) => {

},

getInputFromUser: ({ type, data }) => {

},

endUserSession: () => {

};

};

Brace yourselves! Manually creating such long nodes will look too lengthy. Here's the link to a complete code with the above flow and a sample frontend wrapper - https://github.com/siddug/conversational-trees

The final UI of the same code is hosted here - https://conversational-trees.siddg.com/

I am going to stop here, but here are the immediate next questions to ask:

- If, in the middle of the chat, you reload the page. How do we restore the chat? - We can store the data store but that only restores the "learnings" so far. But doesn't remember which node under which node under which node is the current active node. How do you solve this? Hint- each node name is different at each manager.

- What if the front end malfunctions and resends input for the old node? Hint- each expectation can have a unique id generated from stringing together the node names from the root to reach the node that produces the expectation.

There are more such questions to ask in a real system-

- How can you "time" each question? So that the tree automatically moves to the next node if the user doesn't answer in time.

- How can you have asynchronous operations inside the tree? For example, an open AI GPT call to generate the output?

- And so on

All good questions to extend the functionality of such a system. But one interesting question is,

How do you make creating such systems realistic? Your content team will likely enter question data in a simple JSON format. How do we club these JSONs to create the nodes automatically?

If you want to see a real life version of a bot in it’s full glory - check our bot at www.adaface.com.

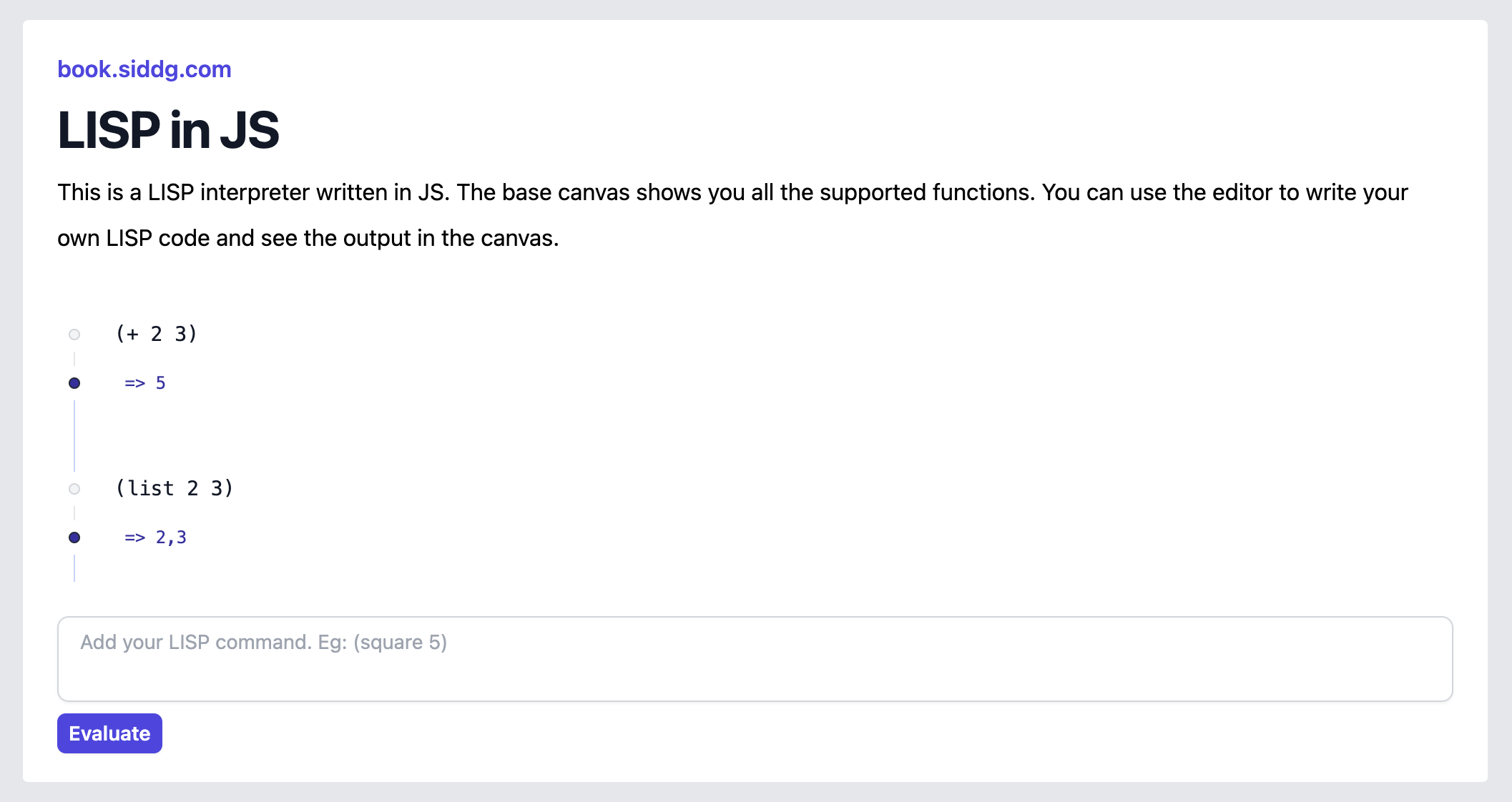

LISP in JS (Creating a new programming language)

Ever thought of creating your own programming language? It is not as daunting as it sounds. Here's my walkthrough of creating LISP, our new language, on top of JavaScript.

Before I kick off, a short note: I have written this content to go along with my book. You can read the current version of the book (including this chapter) here - inconsistent-math-to-live-by.

Back to business:

2011. After my first LISP class, I was very intrigued by this new programming language. There was a beauty to it that I couldn't explain. It was one of the courses that I made sure not to miss.

In the last decade, I have learnt many languages. Programming languages kept getting fancier, like the laptops we use. With each new language, there is increasingly more noise about how to use it. There are many courses on "How to be great at this shiny new language". Without realizing it, we are creating a cloud over the crux of programming language. We are indirectly saying a programming language is mysterious—something you can only use but can't understand.

And that's what we are doing wrong to new developers and engineers. Once you lift that mysterious air about a language and take peek behind the curtain, I believe, you can learn and code in any programming language.

For me, that happened with LISP. LISP was what made me see the beauty of a language. The more I understood it, the more I felt comfortable with the concept of a programming language. LISP is rarely used these days. But for this post, it is perfect. I have an incentive to revisit fond memories of the language while recreating it in JS.

Here's what we will do: we build LISP (a new language) on the bed of JS. By doing that, I hope you get comfortable with the concept of a programming language. While we practice creating something from atoms, under the hood, I hope you appreciate the recursiveness of programming languages.

A short history

At the crux of a computing machine, we have memory and instructions. There are different forms of memory (cache, in-memory, disk etc.), but they all provide a way to store, update and read data. Then we have instructions that make the machine perform low-level operations and move data in memory around.

At the lowest level, we have binary code. These instructions are incredibly basic and limited, such as "add these two numbers" or "move this value from this memory address to another". Writing binary directly is impractical, so assembly language was developed. Assembly gave names to the various binary instructions (such as "ADD" or "MOV") and allowed us to write in a slightly more human-readable form.

Assembly, however, is still rather unwieldy and directly tied to the architecture of the specific processor you're programming for. Therefore, higher-level languages were developed that abstract away a lot of these details. Languages such as C allow you to write code that looks nothing like Assembly, but can still be compiled into it. Higher-level languages like Python, Ruby, or JavaScript offer even more abstractions.

In a sense, each language is built on top of at least one other layer (machine code), providing an increasing level of abstraction and ease of use. So here's where we start our journey. How about we build a language on top of one we already know?

LISP syntax

Here's the LISP syntax we want to support: (You can visit list-js.siddg.com on the side and execute these statements to become friendly with the syntax)

; This is a comment. Every thing that starts after semicolon is a comment.

(+ 2 3)

; every statement in LISP starts and ends with a bracket.

; each statement is a function.

; the contents of a statement start with the function name

; and rest are it's arguments

; (+ 2 3) => a function with name + and 2 and 3 as arguments.

(list 2 3)

; lists are fundamental atoms of LISP

; other fundamental atoms are numbers, strings, "symbols"

; a way to create a list is to call a function with name 'list'

; (list 2 3) => list with elements 2 and 3.

(list 1 (+ 2 3) 4 "sid")

; notice that you can nest statements

; (list 1 (+ 2 3) 4 "sid") => list with elements 1 5 4 "sid"

(first (list 1 2 3))

; first fn returns first element of the list

; (first (list 1 2 3)) => 1

(rest (list 1 2 3))

; rest fn returns rest of elements of the list after first.

; (rest (list 1 2 3)) => list with elements 2 and 3

(cons 2 (list 1 2 3))

; cons fn adds the first element to a list

; (cons 2 (list 1 2 3)) => list with elements 2 1 2 3

(length (list 1 2))

; length fn returns #elements in the list

; (length (list 1 2)) => 2

(> 2 4)

; > function behaves how you would expect it works on binary

; (> 2 4) => false

; so far we have seen base atoms

; and base functions/symbols that we want to support

; all of these base functions do not affect memory

; now let's provide a way to write and read from memory

(let ((x 10) (y 20))

(+ x y))

; let allows a way to set value to symbols and reuse them in a deeper statement

; above statement should return 30

; note that this way to set value to symbols is temporary

; symbols/ functions x and y doesn't mean anything outside 'let'

; that is where symbol set comes into the picture

(set x (list 1 2 3))

; function set takes a symbol and assigns it the value of the first argument

; (set x (list 1 2 3)) => x is saved as list with elements 1, 2, 3

; now we give a way to skip portions of code

(if (> 2 4) "two is > 4" "lesser")

; if is a symbol/ function that takes in 3 arguments

; first argument evaluates to either true or false

; depending on the response, second or third argument is returned

; now we have seen base symbols that affect memory

; now we empower the user of language by giving a way to define their own atoms

(define (square x) (* x x))

; define takes in a series of statements as arguments

; the first statement gives a function name and arguments of fn

; the rest of statements are the function body

; the result of the last statement in body is returned

; once a new symbol/ fn is defined, it is saved in memory so it can be used

(square 2)

; since square is defined above.

; (square 2) => 4

(set x 40)

(square x)

; => 1600

; and that's it. once we empower user with a way to create their own atoms

; they can chain, nest and build complex programs. here are some examples:

(define (sum-of-squares x y)

(+ (square x) (square y)))

(sum-of-squares 3 4)

; => 25

(define (! x) (if (< x 1) 1 (* x (! (- x 1)))))

(! 5)

; => returns 5!

(define (fibo x) (if (or (eql x 0) (eql x 1)) 1 (+ (fibo (- x 1)) (fibo (- x 2)))))

(fibo 10)

; returns 10th fibonacci number

(define

(reverse lst)

(if (eql (length lst) 0)

(list)

(append (reverse (rest lst)) (list (first lst)))

)

)

(reverse (list 1 2 3 4 5))

; => list with elements 5, 4, 3, 2, 1

Get comfortable with the syntax of our new language. Once you are done, let's get cracking.

Let's define our goal: Given a LISP code as input, we want JS to "understand" the passed input and execute those instructions. i.e., perform changes to the memory and run computation operations.

We split this job into three tasks:

- Parser: takes one big string with multiple LISP strings and breaks them down into a list of individual LISP strings.

- Tokenizer: takes a LISP string, breaks it down and creates a token tree.

- Interpreter: takes a tokenized string + memory and evaluates the string (i.e., support all the syntax forms we discussed above)

Parser

Here’s our Parser code: (the comments explain how it works)

/*

Given lisp code,

1. Parse it into well-formed individual statements

2. Use tokenizer to tokenize each statement

*/

function parser(lisp) {

// let's remove comments

// comment starts with ; and can appear in any line.

lisp = lisp

.split("\n")

.map((x) => x.split(";")[0])

.join("\n");

// let's convert lisp into well-formed individual statements

// (+ 2 3) -> well-formed individual statement

// (list 2 3) -> another well-formed individual statement

// simple brute-force algorithm to parse the lisp code character by character

// and splitting based on open and closing brackets

var statements = [];

var openBrackets = 0;

var currentStatement = "";

for (var i = 0; i < lisp.length; i++) {

var token = lisp[i];

currentStatement += token;

if (token === "(") {

openBrackets++;

}

if (token === ")") {

openBrackets--;

if (openBrackets === 0) {

statements.push(currentStatement);

currentStatement = "";

}

}

}

if (openBrackets !== 0) {

throw new Error("Unbalanced brackets");

}

if (currentStatement.length > 0) {

statements.push(currentStatement);

}

// now we have individual well formed statements to work on

// we will use tokenizer to tokenize each statement

// ... to be continued

}

Now that we have an individual LISP statement, we need a tokeniser that converts it.

Tokenizer

Before we start coding, let's think about what we want the tokenizer to do.

Given a statement like ( …. some tokens…. (….some tokens….) (….some tokens…)), we want to split this into an array of children where each child is a token. If the token is a statement, we want the tokenizer to go one level down and tokenize it. If the token is not a statement, we analyze if it is a literal (number or string) or a symbol (a symbol has a meaning/ value from memory).

So (list 1 2 (list 3 (+ 4 5)) 6) should be converted into

[

{ children ->

list -> symbol

1 -> number

2 -> number

{ children ->

list -> symbol

3 -> number

{ children ->

+ -> symbol

4 -> number

5 -> number

}

}

6 -> number

}

]

You can check the first array logged into the console in lisp-js.siddg.com. It contains a list of LISP statements and their tokenized statements.

Once you understand the structure of what we want, here's the tokenizer code:

/*

Given a series of tokens,

(+ 2 3) -> well-formed individual statement also works as list of tokens

// + 2 3 -> list of tokens

// list 1 2 "sid" (list 1 2) -> list of tokens

process it from left to right and return a array of analyzed tokens

// supported tokens

// 1. number

// 2. string

// 3. symbol --> anything that is not number of string or a bracket

// whenever a ( is encountered, tokenize the list of tokens inside the bracket into a separate object

*/

function tokenizer(seriesOfTokens) {

if (seriesOfTokens.length === 0) {

return [];

}

// The first token in the list is a well-formed individual statement

if (seriesOfTokens[0] === "(") {

// find the closing bracket

var openBrackets = 0;

var closingBracketIndex = -1;

for (var i = 0; i < seriesOfTokens.length; i++) {

if (seriesOfTokens[i] === "(") {

openBrackets++;

} else if (seriesOfTokens[i] === ")") {

openBrackets--;

if (openBrackets === 0) {

closingBracketIndex = i;

break;

}

}

}

// list of tokens inside this bracket

var tokensOfthisBracket = seriesOfTokens

.substring(1, closingBracketIndex)

.trim();

// rest of the tokens;

// remember seriesOfTokens might not be a well-formed individual statement.

// so there can be more tokens left to process.

// example if the original statement sent to tokenizer is (list 1 2) 3 4

// then we are going to tokenize (list 1 2) and 3 4 separately

var restOfTheTokens = seriesOfTokens

.substring(closingBracketIndex + 1)

.trim();

return [

{

children: [...tokenizer(tokensOfthisBracket)],

},

...tokenizer(restOfTheTokens),

];

}

// The first element in the list is the tokens is a string.

// strip the string and tokenize the rest of the tokens

if (seriesOfTokens[0] === '"') {

return [

{

type: "string",

stringContent: seriesOfTokens.substring(

1,

seriesOfTokens.indexOf('"', 1)

),

},

...tokenizer(

seriesOfTokens

.substring(seriesOfTokens.indexOf('"', 1) + 1)

.trim()

),

];

}

// Not a string. Not a (). What else could it be? analyze first word

var firstSpaceIndex = seriesOfTokens.indexOf(" ");

if (firstSpaceIndex === -1) {

firstSpaceIndex = seriesOfTokens.length;

}

var firstWord = seriesOfTokens.substring(0, firstSpaceIndex);

var restOfTheTokens = seriesOfTokens.substring(firstSpaceIndex + 1).trim();

if (!isNaN(firstWord)) {

// it is a number

return [

{

type: "number",

number: Number(firstWord),

},

...tokenizer(restOfTheTokens),

];

}

// it is a symbol. return it as it is. tokenizer is not smart enough to analyze what it is.

// it just says it is something to analyze

return [

{

type: "symbol",

symbol: firstWord,

},

...tokenizer(restOfTheTokens),

];

}

Note here that the tokenizer always returns an array of tokens. But when we pass a well-formed statement, we expect an object with children instead of an array. We adjust for this when we pair the parser with the tokenizer. Here's the completed parser code:

/*

Given lisp code,

1. Parse it into well-formed individual statements

2. Use tokenizer to tokenize each statement

*/

function parser(lisp) {

// let's remove comments

// comment starts with ; and can appear in any line.

lisp = lisp

.split("\n")

.map((x) => x.split(";")[0])

.join("\n");

// let's convert lisp into well-formed individual statements

// (+ 2 3) -> well-formed individual statement

// (list 2 3) -> another well-formed individual statement

// simple brute-force algorithm to parse the lisp code character by character and splitting based on

// open and closing brackets

var statements = [];

var openBrackets = 0;

var currentStatement = "";

for (var i = 0; i < lisp.length; i++) {

var token = lisp[i];

currentStatement += token;

if (token === "(") {

openBrackets++;

}

if (token === ")") {

openBrackets--;

if (openBrackets === 0) {

statements.push(currentStatement);

currentStatement = "";

}

}

}

if (openBrackets !== 0) {

throw new Error("Unbalanced brackets");

}

if (currentStatement.length > 0) {

statements.push(currentStatement);

}

// now we have individual well formed statements to work on

// use tokenizer to tokenize each statement

var tokenizedStatements = statements

.filter((x) => x)

.map((x) => x.trim())

.filter((x) => x)

.map((statement) => {

var tokens = tokenizer(statement);

var tokenizedStatement = {

children: tokens,

}; // OR tokens[0]

// interpreter works on whole formed individual statements that are represented by objects

// tokenizer returns a list of tokens which themselves are objects

// so we can either send tokens[0] as the statement to interpreter

// OR

// form a wrapped object with children as tokens and send it to interpreter

// we are doing the latter because it is fun

return {

statement,

tokenizedStatement,

};

});

return tokenizedStatements;

}

You can use our parser (with tokeniser inside) like this:

var lisp = `

(+ 2 3)

`;

const parsedOutput = parser(lisp);

console.log(parsedOutput);

Interpreter

First, let's build a function 'interpret' that takes in a tokenized statement (object) and works on it. Here's the complete code of this function with proper comments to explain the logic flow:

/*

Given a tokenized statement, interpret/ evaluate it and return the result

env is the environment in which the statement is interpreted

*/

function interpret(statement, env) {

var type = statement.type;

// If we are dealing with atomic step

// i.e, 1 2 3 "sid" list square etc.

// return it's value from environment

if (type === "number") {

return Number(statement.number);

} else if (type === "string") {

return statement.stringContent;

} else if (type === "symbol") {

return env[statement.symbol];

}

// If it is not atomic, then it must have children

var children = statement.children;

// First children gives us the type of the statement to interpret

var firstItem = children[0];

var rest = children.slice(1);

var type = firstItem.type;

if (type === "symbol") {

// If it is a symbol, then it is a special form or a function call

var symbol = firstItem.symbol;

// "rest" then becomes the arguments to the special form or function call

// Special forms that we support

if (symbol === "list") {

return [...rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env))];

} else if (symbol === "first") {

return [...interpret(rest[0], env)][0];

} else if (symbol === "rest") {

return [...interpret(rest[0], env)].slice(1);

} else if (symbol === "last") {

return [...interpret(rest[0], env)].slice(-1)[0];

} else if (symbol === "cons") {

return [interpret(rest[0], env), ...interpret(rest[1], env)];

} else if (symbol === "append") {

return rest

.map((x) => interpret(x, env))

.reduce((a, b) => a.concat(b), []);

} else if (symbol === "length") {

return [...interpret(rest[0], env)].length;

} else if (symbol === "+") {

return [...rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env))].reduce(

(a, b) => a + b,

0

);

} else if (symbol === "-") {

const nums = [...rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env))];

if (nums.length === 0) {

// (-) -> 0

return 0;

} else if (nums.length === 1) {

// (- 2) => -2

return -1 * nums[0];

}

// (- a b c) => a - b - c

return nums[0] - nums.slice(1).reduce((a, b) => a + b, 0);

} else if (symbol === "*") {

return [...rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env))].reduce(

(a, b) => a * b,

1

);

} else if (symbol === "/") {

return [...rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env))].reduce(

(a, b) => a / b,

0

);

} else if (symbol === "%") {

return [...rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env))].reduce(

(a, b) => a % b,

0

);

} else if (symbol === ">") {

return interpret(rest[0], env) > interpret(rest[1], env);

} else if (symbol === "<") {

return interpret(rest[0], env) < interpret(rest[1], env);

} else if (symbol === ">=") {

return interpret(rest[0], env) >= interpret(rest[1], env);

} else if (symbol === "<=") {

return interpret(rest[0], env) <= interpret(rest[1], env);

} else if (symbol === "eql") {

return interpret(rest[0], env) === interpret(rest[1], env);

} else if (symbol === "or") {

return rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env)).some((x) => x);

} else if (symbol === "and") {

return rest.map((x) => interpret(x, env)).every((x) => x);

} else if (symbol === "let") {

const firstRest = rest[0];

const restRest = rest.slice(1);

const newEnv = { ...env };

for (var i = 0; i < firstRest.children.length; i++) {

const child = firstRest.children[i];

const symbol = child.children[0].symbol;

const value = interpret(child.children[1], env);

newEnv[symbol] = value;

}

return interpret(restRest[restRest.length - 1], newEnv);

} else if (symbol === "set") {

const firstRest = rest[0];

const restRest = rest.slice(1);

const symbol = firstRest.symbol;

const value = interpret(restRest[0], env);

env[symbol] = value;

return value;

} else if (symbol === "define") {

const firstRest = rest[0];

const restRest = rest.slice(1);

const fnName = firstRest.children[0].symbol;

const fnArgs = firstRest.children.slice(1).map((x) => x.symbol);

const fnBody = restRest[0];

env[fnName] = {

fnArgs,

fnBody,

};

return fnName;

} else if (symbol === "if") {

const firstRest = rest[0];

const secondRest = rest[1];

const thirdRest = rest[2];

const condition = interpret(firstRest, env);

if (condition) {

return interpret(secondRest, env);

} else if (thirdRest) {

return interpret(thirdRest, env);

} else {

return false;

}

} else {

// check if this is a function call

if (env[symbol] && env[symbol].fnArgs) {

const fnArgs = env[symbol].fnArgs;

const fnBody = env[symbol].fnBody;

const newEnv = { ...env };

for (var i = 0; i < fnArgs.length; i++) {

newEnv[fnArgs[i]] = interpret(rest[i], newEnv);

}

return interpret(fnBody, newEnv);

} else {

return env[symbol];

}

}

} else {

return interpret(firstItem, env);

}

}

Spend some time going back and forth between this code and the sample statements provided in lisp-js.siddg.com. The 'aha' moment comes when you understand how a new environment is spawned to make 'let' work. Then the bigger 'aha' comes when you understand how we make 'define' work to define a new user-defined function. And you are then giving the user ability to execute their functions along with passing data to their functions on-demand.

If you notice our parser, it returns a list of tokenized statements. Whereas our 'interpret' works on a single tokenized statement. Here's a wrapper (with some added functionality of showing us intermediate memory):

// Given a list of parsed statements, interpret them and return the result

// env is the environment in which the statements are interpreted

// for debugging purposes, we can pass debug=true to get the environment at each step

function interpreter(parsedStatements, env, debug) {

return parsedStatements.map((s) => {

const eval = interpret(s.tokenizedStatement, env);

return {

...s,

eval,

...(debug

? {

env: JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(env)),

}

: {}),

};

});

}

That’s it. You can use our parser (with tokenizer) + interpreter like this:

var lisp = `

(+ 2 3)

`;

var env = {};

const interpretedOutput = interpreter(parser(lisp), env, (debug = true));

for (const x of interpretedOutput) {

console.log(`${x.statement} => ${x.eval}`, x.env);

}

You can find the complete code (index.js) at https://github.com/siddug/lisp.js

It also has the HTML file that renders list-js.siddg.com, which uses our LISP-in-JS code to create an interactive editor.

Closing

Technically this new "language" is no different from the languages you learn and use today. We can create a few more special forms of this language to access the HTML DOM to make it more functional. We can create documentation, tutorials and the whole bazinga. With enough craze and popularity, everyone would use our new language and forget that it is simply an abstraction. And with that, I finish my Sunday meditation.

If you are still reading, thanks for hanging out with me. I hope you got something out of this. Here are some practice problems if you want to spend some time in the LISP-in-JS world before we head back to our daily "real" work.

/*

practice problems (doesn't require new syntax)):

- Find kth element of a list

- Find if a list is a palindrome

- Find index of an element in list

- Find minimum of an element in list

- Find if a list is sorted

- Find if a list has an element in it

- Intersection of lists

practice problems (add loop syntax):

- Find if a number is a prime

practice ux problems:

- Given a proper list statement, pretty print it with proper indentation (raise a PR to the repo)

practice library problems:

- Add forms to enable lisp-js to access DOM (example: (document.getElementById "id"))

*/

More curious?

- Want to try the old-school LISP or its variants? Replit has a functional Emacs LISP setup - here's the link.

- Curious if anyone is using LISP? - here's a post from the Grammarly team talking about running LISP in prod.

- If this post is trippy and you can use a conversational chat instead - I am planning a course on a few of these topics. Hit me up.